Besides the auditing trail of all the changes made against a database and having the information of who committed what and when, the main benefit of having a database under version control is the fact that the history of all the previously committed versions of any object (or a group of objects) can be used to find the exact version that broke the database at any point. Assuming that a SQL database under source control is being deployed on a daily basis or even more frequently, it is essential to ensure that only tested changes are committed so that a SQL database can be deployed in a working state, without any issues.

However, real-world scenarios of having a team of developers making a large number of changes and committing those changes to source control, cannot guarantee that there will be no changes that will at some point break a database, even when such changes are tested. A responsible team is not the one that just ensures good changes are versioned in source control, but also ensures that in case a SQL database deployment from source control fails for any reason, the problematic change is found as soon as possible and reverted or fixed in any way possible.

Challenge

The challenge is to have a mechanism available, to easily review committed changes, to be able to filter out committed changes in order to narrow down the list to the most recent changes, or changes committed during the specific period of time. In addition to this, once the version of an object that caused a problem is found, the solution must ensure an easy way to revert back to the previous version, or any other older version that worked, to be pulled from the history and applied against a database. In this way, we can ensure that the SQL database deployment will succeed on the next run.

Problem

The first problem is if a database is not being version controlled. We won’t go into details here about the exact issues. It is enough to mention that either a team needs to script out and keep each and every version of an object that is changed. Those scripts must be on a shared location, so all team members could access them in order to review and eventually revert back to any of the previous version in case there is a need.

Having a SQL database under source control is a huge step ahead in resolving the problem. However, a few potential issues need to be covered with a solution.

When dealing with team-based development that includes a large number of committed changes, it is essential to ensure that browsing through the history is fast and that changesets can be filtered out in a way to show changesets committed:

- at a given period of time (today, yesterday, etc.)

- by the specific developer

- at the specific time frame (this week, last week, etc.)

And any and all of the above, in combination.

Another important part is that, even if the history of all committed changes exists and developers are able to review any version of an object, when it comes to reverting back any previous version of an object (or a group of objects) it is mandatory to keep the referential integrity of a database unaffected. That means that when reverting back a previous version of an object from source control history, any dependent objects should be properly scripted and included in the script with the exact order of the execution. This is a critical point since it can cause additional problems with a database that will, for sure require additional troubleshooting.

Pre-condition

For the purpose of this article, we’ll assume a database is linked to source control using ApexSQL Source Control, a SQL Server Management Studio add-in that allows seamless integration with source control systems such as Git, Team Foundation Server, Subversion, Mercurial and Perforce.

All objects from a sample database (called DB_Prod in our example) are initially committed and developers already made a bunch of changes committing them to source control. So, we’ll jump in the middle of the SQL database development process at the point where the particular change committed by one of the developers caused a SQL database deployment to fail. To illustrate this, we have a simplified environment with only three developers working on a database and a number of changes (much smaller than it would be in real scenario) committed to a Subversion repository.

Let’s assume that the latest nightly build failed and a team got the error message from the CI mechanism that was sent to a lead developer, saying that a SQL database build failed due to a specific error (missing CategoryGroup column from the Category table). Since the goal of this article is to show how to find the specific object in history and to revert an object to a previous version, we won’t go into details about the error. Let’s say that the Category table was changed a day before a nightly build fail (October 31st) causing the SQL database build process to fail.

Solution

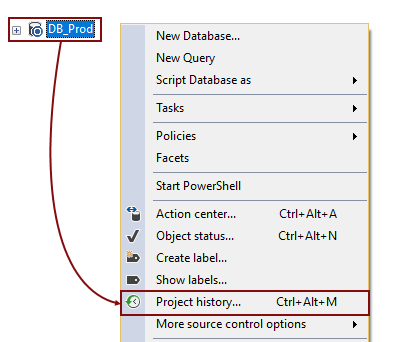

Let’s review the history of committed changes using the Project history option from the Object Explorer context menu:

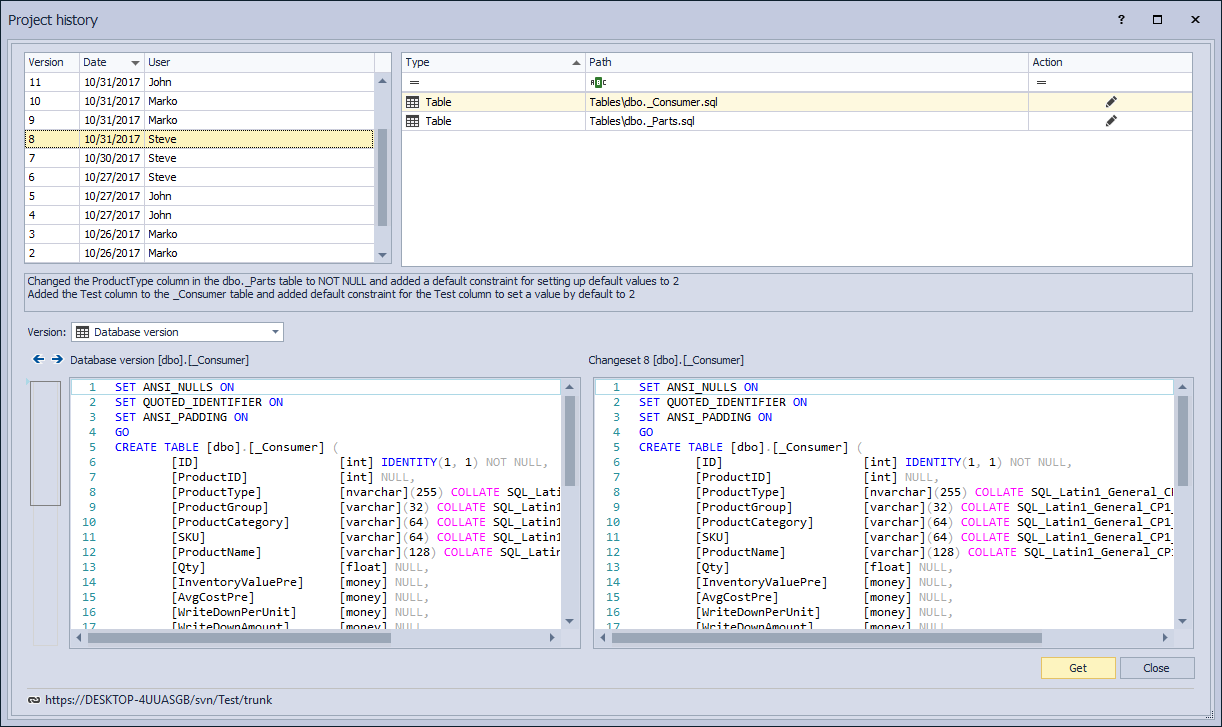

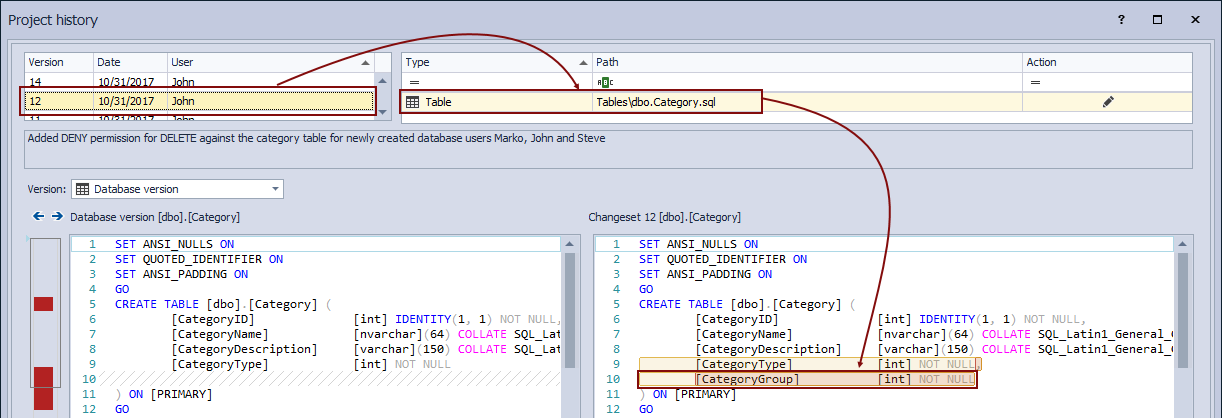

This opens the Project history window showing all committed changesets including what is committed in which changeset:

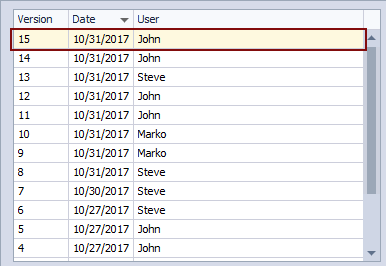

In the upper left section of the Project history dialog, a list of all committed changesets will be shown. By default, a list is chronologically sorted, with the most recent changeset shown on top (in this case Changeset 15 committed by John):

When highlighting any of the changesets from the list, objects from the highlighted changeset are shown on the right, while the commit message is shown below:

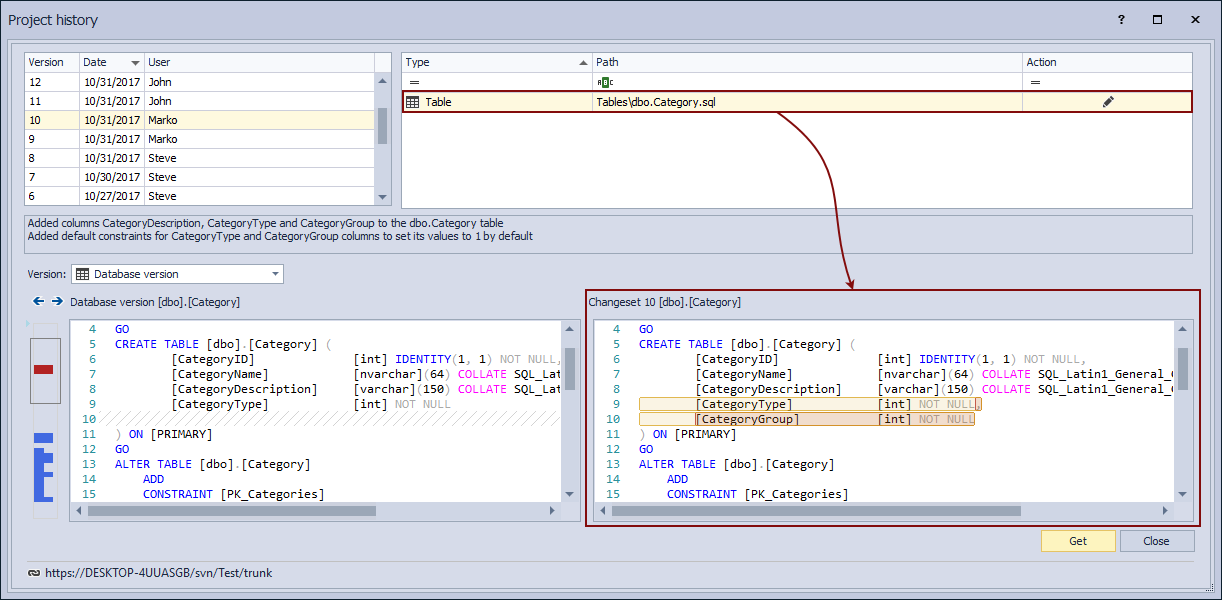

Highlighting any object from the list on the right shows the exact version of an object in the lower right section (in this case the only object in Changeset 10 is the Category table):

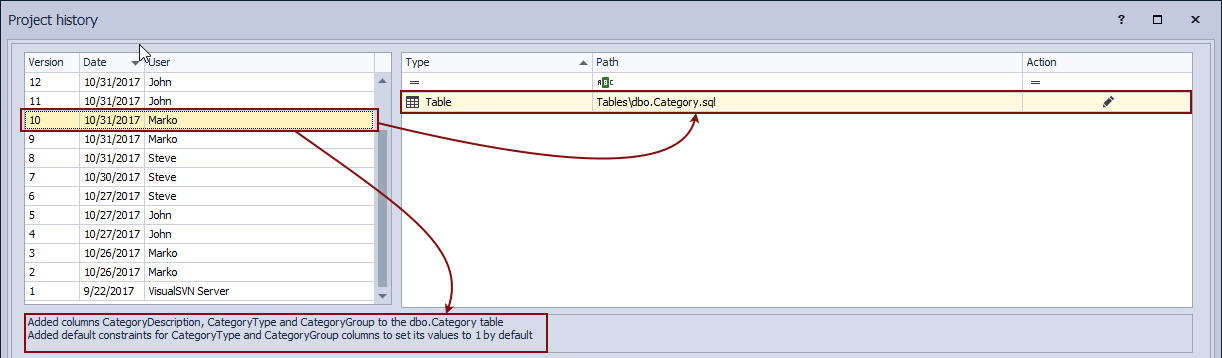

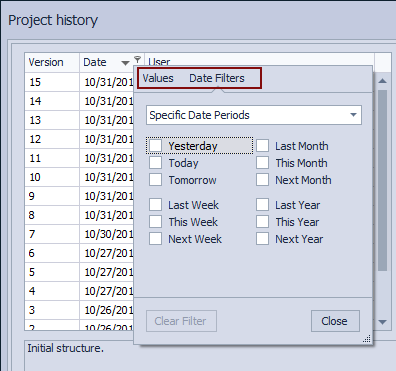

Let’s try to find who changed the Category table on October 31st so we can narrow our troubleshooting. In order to narrow down the list of committed changes, we’ll use the date filter in the upper left section of the Project history dialog:

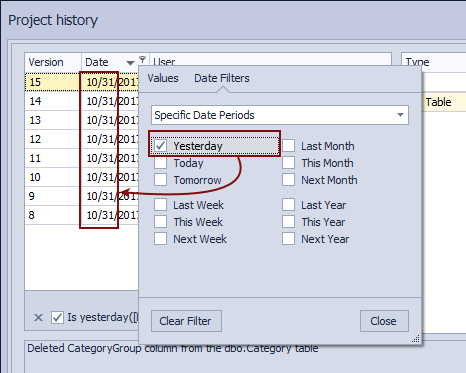

Using the filtering options, we can easily filter only changesets committed on October 31st. Assuming that we are troubleshooting this a day after the issue is encountered, we can check the Yesterday field. As soon as any of the above is used, we’ll get a list of committed changesets on this date:

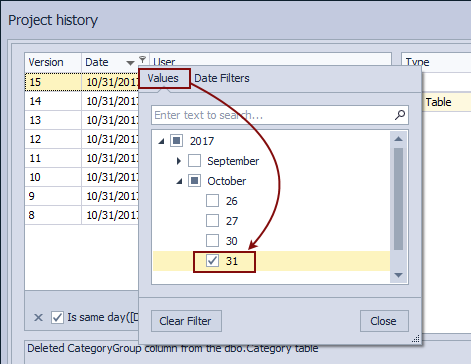

Similar to this, we can pick specific date under the Values tab:

In this way, we have easily shown all the changesets committed at the specific date that we need to review. Similar to this, any other date or a date range can be specified to narrow down the list of committed changesets.

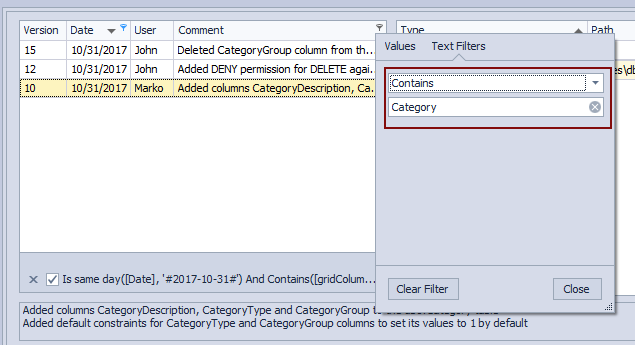

Now that we have all changesets committed on a day when an error is encountered, let’s find out who changed the Category table. Assuming that developers are specifying valid and descriptive commit messages that include the information about which objects are modified, we’ll search through the commit messages for the Category keyword. In order to do so, we’ll use the filter from the Comment column searching for all comments that contain the Category keyword:

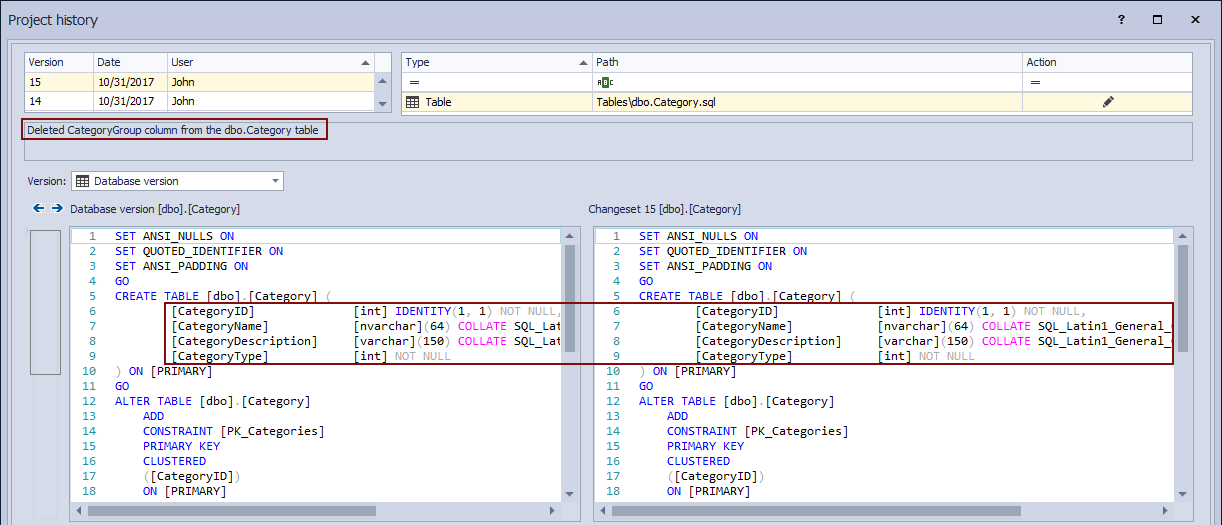

This will narrow down a number of possible changesets (in our case to three changesets). At this point, we can either review all of these to find out the exact issue or we can use additional filters to reduce this number. Let’s say that we have found a changeset that broke the database, based on the outputs we have got from the build server. Changeset 15 contains changes related to the Category table that was the breaking change. To review what was committed in Changeset 15, we’ll highlight it in the upper left section:

We can confirm from the SQL script shown in the lower right section that the CategoryGroup column is missing. In addition to this, a commit message informs us that the CategoryGroup column was dropped and such change was committed in Changeset 15.

Now that we have found what broke the database, let’s try to fix the problem.

We’ll need to find the most recent version of the Category table where the CategoryGroup column exists. Currently, the script differences section shows no differences, as we are comparing a version of the Category table committed in Changeset 15 (on the right side) with the current version of an object in a database (Database version on the left):

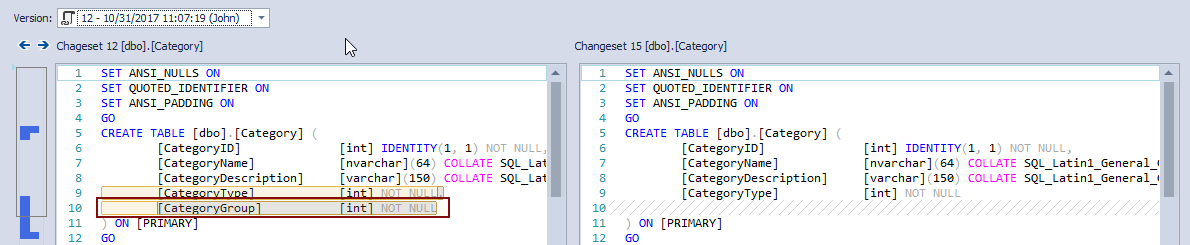

Expanding the drop-down list on the left side, we’ll see each and every version of the Category table that is committed to source control. This means some of these versions will be the one we should revert back from history. We’ll pick the previous version, which is in Changeset 12:

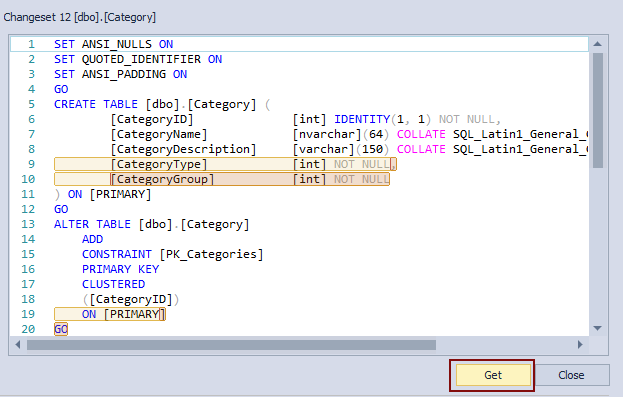

We can confirm that the CategoryGroup column that was missing actually exists in Changeset 12. Let’s set Changeset 12 as the current one, so we can revert back objects from that changeset:

Now, we have the Category table with the CategoryGroup column on the right side and a version of the Category table without the CategoryGroup column. In order to apply a version from Changeset 12, we’ll click the Get button in the lower right corner of the Project history window:

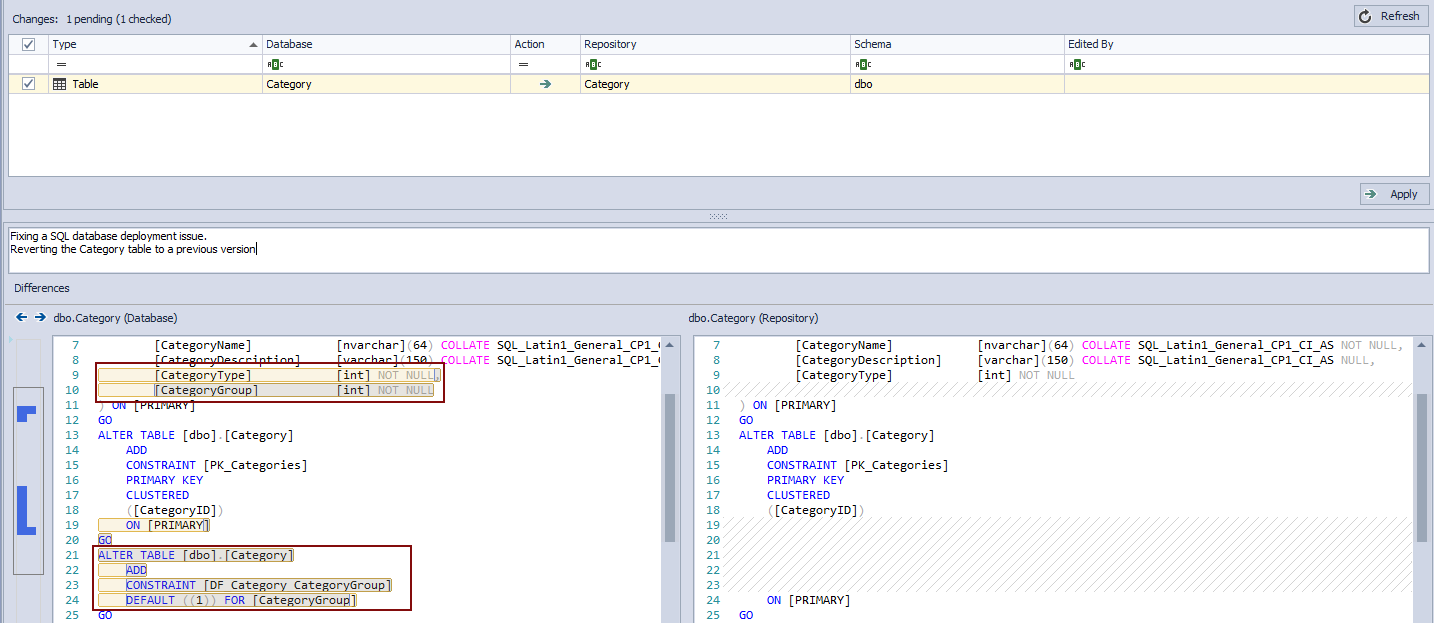

ApexSQL Source Control will process all database objects, taking care of SQL database referential integrity. As a result, a synchronization script will be created, not just to add the CategoryGroup column, but to re-create or alter any dependent objects to include the new change. Once the previous version is applied to a database, we’ll have the following in the Action center tab:

Besides the CategoryGroup column, ApexSQL Source Control pulled a default constraint that was created for the CategoryGroup column and committed within the same changeset. After pushing this change to source control, we can be sure that the same error won’t happen.

Conclusion

It is essential, for rapid and responsive troubleshooting, to establish an efficient mechanism for reviewing committed changes as well as a mechanism to apply the previous version of an object to a database. The task can be challenging when a team of developers is committing a large number of changes on a daily basis. Digging through the commit history, as part of a forensic process, in search for an object which broke the database should take as short as possible. With ApexSQL Source Control, this can be a matter of minutes, even with a large number of objects and changesets committed to source control.

November 1, 2017